Does Paying Taxes Destroy Money?

At the Fiscal Sustainability Conference in 2010, Dr. Stephanie Kelton asserted that when the US Government collects taxes, it obtains nothing it can turn around and spend, nothing but the extinguishment of its own IOU. And she asserted that when the payments are made in cash, the US Government sends the cash to the Fed, which shreds it without booking it.

Paying taxes destroys money. It doesn’t give the government anything. It doesn’t get anything. It eliminates those liabilities. They are, for all intents and purposes, destroyed. [00:18:06]

That’s if you pay with a check. What would happen if you actually sent the government your cash? Every once it awhile it seems like you hear about some crazy person who does this in protest. They get a huge sack, usually of coins just to make it really offensive and difficult on some poor bean counter. Let’s say you have a tax liability and it’s a hundred dollars and you just mail in a one hundred dollar bill. Apart from the shock of opening the envelope, what are they going to do with this? What do we do with this? Send it to the Fed. That’s where the Treasury banks. Goes to the Fed, and what do they do with it? They shred it. They shred it. Why would they shred it, I mean literally shred it, if they needed it to buy things, if they could use it to spend? Because they don’t use it to spend and they don’t need it to buy things. [00:19:06]

So why bother collecting taxes at all, if the government doesn’t need our money, and this came up earlier. Lynn raised this question. Why bother collecting taxes? When we pay our taxes, whether by cash or by check, all we’re doing at the end of the day, is returning to the government its own liabilities. That’s all we’re doing. And they say, ‘Thank you very much’, and the transaction is done. They don’t get anything that they can turn around and spend. They get their own IOU back from us. That’s the end of the transaction. [00:19:40]

So, why do it? Two reasons. One is, and this goes back to the Modern Money Theory that I began with, one is that taxes give value to the government’s money. If they were just to say, ‘We don’t need taxes in order to spend, so let’s suspend all collection of taxes’, that would undermine the value of the currency. It would take away the need that we have to acquire the government’s money. Why would we work and produce things for the government? Why would the government be able to move resources from the private sector to the public domain if it can’t get us to do that by virtue of the fact that we are willing to work and provide things to get the government’s liabilities? So, taxes maintain a demand for the government’s currency – that’s important – and the other thing they do, is they allow the government to regulate aggregate demand. Too much spending power can be inflationary, too little causes unemployment and recessions. [00:20:42]

Dr. Stephanie Kelton at Fiscal Sustainability Conference 2010 (Part 3)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1quunEJz3RY

(Original transcription from CorrenteWire, no longer posted. Emphasis mine.)

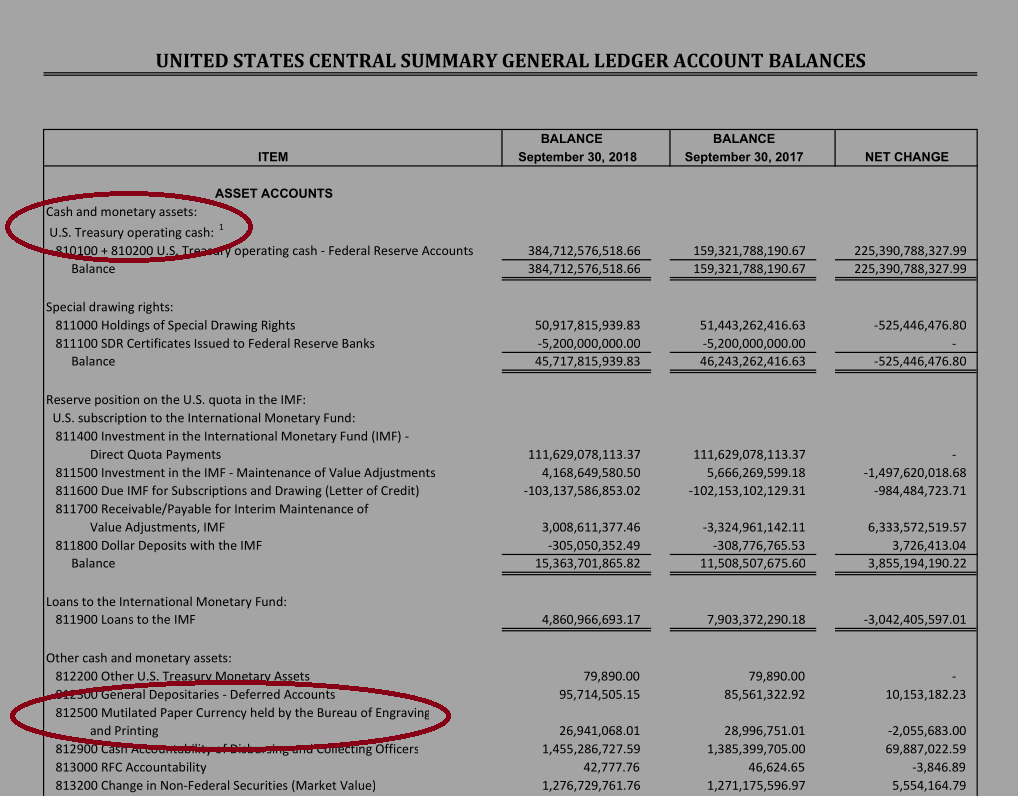

Was Dr. Kelton’s depiction accurate? I looked to the public documents to find out. Here’s an image of a page from the US Governments Summary General Ledger as of September 30, 2018. Just a three page document.

via https://www.fiscal.treasury.gov/files/reports-statements/combined-statement/cs2018/sc1.pdf

As highlighted, cash is an asset to the US Government. And in item 812500 we see my favorite ledger entry: even Mutilated Paper Currency is an asset to USG. Almost $27m as of September 2018. I do wonder how they managed to book that extra penny. Nonetheless, consider. Dr. Kelton says the US Government shreds paper currency as a redeemed liability. The General Ledger shows that the US Government retains mutilated paper currency as an asset, collectively valued at almost $27 million. Which account should we believe?

And why indeed, as Dr. Kelton asks, “would they shred it, I mean literally shred it, if they needed it to buy things, if they could use it to spend?” Answer is: they don’t. USG agencies follow the instructions in the Treasury Financial Manual (Section 2030). They deliver currency receipts to a “commercial bank authorized to accept TGA (Treasury General Account) deposits.”

Whereupon said currency is accepted for deposit at the commercial bank, then intermixed with currency from supermarkets, bowling alleys and laundromats, and bundled by tellers for the bank’s customers. Some of it is returned to a Federal Reserve Bank, not for extinguishment but for credit to the commercial bank’s reserve balance. While the Government retains an asset entirely disconnected from the deposited currency: the IOU of the commercial bank, which will soon be obliged to assign some of its own reserve balances to the Treasury General Account to satisfy its liability.

I would thus argue that Dr. Kelton has used a false operational depiction to support a false accounting depiction.

Dr. Kelton depicts the payment of federal taxes as redemption to the US Government of the US Government’s own IOUs, much as a cloakroom receives and reuses its own tokens, as a railroad receives and destroys its own tickets, as a casino receives and reuses its own chips, or as Mr. Mosler receives and reuses his own otherwise worthless business cards. Taxes are for redemption, not spending is MMT’s canonical claim, and redemption is the basis for Dr. Kelton’s claim that paying taxes destroys money.

We’ve shown that at an accounting level, the US Government books tax receipts as assets, unlike any economic actor that receives its own IOUs in trade. Moreover, at an institutional level, paper currency is depicted as the liability of a consortium, the Federal Reserve Banks, whose members assert or acknowledge that they are not part of the US Government. We’ve also shown that Dr. Kelton’s operational depiction, whereby currency received in the course of Federal taxation is returned to the Federal Reserve Banks for destruction or reuse without any recorded financial benefit to the US Government, is inconsistent with the procedures described in the Treasury Financial Manual, under which currency received by US Government agencies is to be deposited into local commercial banks for credit to USG accounts.

Both aggregate reserve balances (reflecting cash assets of the taxpayer’s bank) and the money supply M1 (reflecting liabilities of that bank) are drawn down in the process of Federal tax collection, but ultimately only one cash account is credited: the Treasury General Account, a liability of the Federal Reserve Bank of NY. Dr. Kelton relies upon this fact to conclude that taxation cannot be a source of revenue for the “consolidated” US Government, imagined to include the Reserve Banks.

But in support of her assertion that paying Federal taxes destroys money, Dr. Kelton describes a process that, upon closer inspection, constitutes the redemption of commercial bank IOUs, not U.S. Government IOUs.

The net financial balances of both the taxpayer’s commercial bank and the Reserve Banks are unchanged as the Federal Government collects upon a tax payment. The commercial bank has been disintermediated; both its assets and liabilities have diminished. The Reserve Bank’s liabilities have been reapportioned in favor of the US Government: out of the reserve account of the taxpayer’s bank and into the Treasury General Account. While the TGA is not considered to be part of the nation’s money supply, the US Government recognizes tax receipts on its General Ledger as an augmentation of its most liquid asset, cash.

Here’s the parallel. When we withdraw currency at an ATM and our checking balance is reduced accordingly, have we not destroyed money by the same standard Dr. Kelton applies to the payment of Federal taxes? We’ve redeemed a portion of the commercial bank’s debt to us, just as the taxpayer does when she writes a check to the U.S. Treasury. In the withdrawal, both M1 (which includes our checking balance) and Reserve Balances (which include our bank’s vault cash) have been diminished, but only M1 (which includes currency held by the nonbank public) has been augmented.

Similarly, do we not create money by spending it when we make a purchase with currency and the merchant deposits the currency at a commercial bank? One measure of money is diminished, but two are augmented. Indeed, when we pay the National Park admission in currency and the US Government deposits that currency into a nearby commercial bank, the transaction augments both Reserve Balances and USG’s GL asset class cash. Thus we can as easily show that paying federal taxes in currency creates money.

Disintermediation should be distinguished from ultimate net redemption, which occurs, for example, with the U.S. Postal Service cancels a postage stamp – its own IOU – in the course of mail delivery. When we withdraw funds from our own checking account at an ATM, the bank does cancel a portion of its own IOU, but it supplies us with an instrument that it and all other U.S. banks are obliged to accept for deposit, assuring that the monetary effects of the withdrawal can be reversed at the option of each currency holder. Net redemption, like that achieved in transactions with the cloakroom, the railroad and the casino described above, is demonstrated when a commercial bank draws down our checking account to collect a fee. Its balance sheet is enhanced by reducing its debt to us, not by augmenting its assets. Some portion of M1 is destroyed in the process, with no contractual assurance of its re-creation. Similarly, the Federal Reserve Banks redeem — rather than merely reapportion — their own liabilities when they accept them for purchase of U.S. Treasuries or for bank services as are offered at FRBServices.org. Reserve balances are destroyed through this very narrow mechanism of reflux.

Dr. Kelton maintains that the payment of federal taxes similarly represents a redemption of a U.S. Government liability to its issuer, providing the issuer with nothing it can “turn around and spend.” But accounting shows that Federal taxation, contra MMT and with an intermediary step, actually augments the assets of the US Government as it diminishes the assets of the taxpayer.